So, what do you expect to see when you watch an Exodus movie? (1) A Pillar of Fire, (2) A Burning Bush that Talks and is Also God, (3) the Parting of the Red Sea, (4) pre-Freudian rods that turn into pre-Freudian snakes, and (5) at least a couple plagues. This version of Exodus has some of those things, but not all—we’ll get into what it leaves out in a minute. But it also adds a few things that are just fascinating.

Spoilers ahead for the film, but also…it’s Exodus…

Let me preface this review by saying that the day after I watched Exodus, a colleague asked me a difficult question: Is the movie better or worse than the state of contemporary America? I’d have to say…better? But not by much. Two weeks ago I ended up writing a recap of the TV show Sleepy Hollow while the Michael Brown decision came though, and since that show deals explicitly with the racial history of the US, I tried to write about my reaction within that context. Two weeks later I attended a screening of Exodus near Times Square, a few hours after the Eric Garner decision, and when I came out people were marching through the Square and over to the Christmas tree in Rockefeller Center.

I joined them, and it was impossible not to think about the film in this context as I walked. Ridley Scott’s film, which attempts a serious look at a Biblical story of bondage and freedom-fighting, undercuts its own message, tweaks the Hebrew Bible in some fascinating (and upsetting) ways, and comes off as incredibly tone deaf by the end.

So let’s get this out of the way: yes, Exodus is pretty racist. But it’s not nearly as racist as it could have been. Or, rather, it’s racist in a way that might not be so obvious right away. But at the same time—wait, how about this. Let me get some of the film’s other problems out of the way first, and I can delve into the racial aspect in more detail further below.

Can you tell I have a lot of conflicting feelings here?

As much as I’ve been able to work out a overarching theory behind this movie, I think Ridley Scott wanted to one-up the old school Biblical spectacles of the 1950s, while also folding in some of the grit and cultural accuracy of Martin Scorcese’s Last Temptation of Christ and (very, very arguably) Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. This is an interesting idea, and could have resulted in a moving film, but since he doesn’t fully commit to any one thing, the film sort of turns into a weird stew. He checks off the Biblical Epic box by showing the film in 3D. Which, um… have you ever wanted to sit in a movie theater while flies zing past your head? Have you ever wanted to watch the action in a film unfold six yards away, while you crouch behind bushes? Have you ever wanted to look a CGI locust right in the eye? Cause that’s pretty much what the 3D is for here.

Meanwhile, for Grit and Accuracy, the Plagues get (ludicrous) scientific explanations. The battles, starvation, and boils are all depicted as horrific, and Rameses is a terrible despot who tortures and executes people with no concern for public outcry. In a move that also flows into the film’s greatest flaw, all of Moses’ interactions with God are framed as possible delusions. His first interaction with the Burning Bush happens after he falls and whacks his head. His wife tells him it was just a dream, and Moses himself explicitly says he was delusional. The film also gives us several scenes from Aaron’s point of view, in which Moses seems to be talking to empty space. The interpretation rings false. Why make weird gestures towards a critical perspective on the Exodus story but then cast your Egyptian and Jewish characters with white actors?

In Last Temptation of Christ, Martin Scorsese plays with the conventions of old Biblical spectacles and the class differences between Jews and Romans in a very simple way: the Romans are all Brits who speak with the crisp precision of Imperial officers, and the Jews are all American Method actors. This encodes their separation, while reminding us of the clashes between Yul Brynner and Charlton Heston, say, or the soulful Max Von Sydow and the polished Claude Rains in The Greatest Story Ever Told. In Exodus, it can only be assumed that Ridley Scott told everyone to pick an accent they liked and run with it. Moses is… well, there’s no other way to say this: he sounds like Sad Batman. Joel Edgerton seems to be channeling Joaquin Phoenix’s Commodus with Rameses, and uses a weird hybrid accent where some words sound British and some are vaguely Middle Eastern. (Actually, sometimes he sounds like Vin Diesel…) Bithia, Moses’ adopted mom and daughter of the Egyptian Pharaoh, speaks in what I’m assuming is the actress’ native Nazarene accent, but her mother (Sigourney Weaver) speaks in a British-ish accent. And Miriam, Moses’ sister, has a different vaguely British accent. Ben Kingsley sounds a bit like he did playing the fake-Mandarin. God speaks in an infuriating British whine. Where are we? Who raised whom? Why don’t any of these people sound the same when half of them live in the same house?

We also get the De Riguer Vague Worldmusic Soundtrack which has been the bane of religious movies since Last Temptation of Christ. (For the record, LTOC is one of my favorite movies, and Peter Gabriel’s score is fantastic. But I’ve begun to retroactively hate it, because now every religious movie throws some vaguely Arabic chanting on the soundtrack, and calls it a day.) Plus, there are at least a dozen scenes where a person of authority orders people out of a room, either by saying “Go!” or simply waving their hand at the door. While I’m assuming this was supposed to be some sort of thematic undergirding for the moment when Pharaoh finally, um, lets the Hebrews go, it ended up coming off more as an homage to Jesus Christ Superstar. And speaking of JCS…. we get Ben Mendelsohn as Hegep, Viceroy of Pithom, the campiest Biblical baddie this side of Herod. That’s a whole lot of homage-ing to pack into a film that’s also trying to be EPIC and SERIOUS.

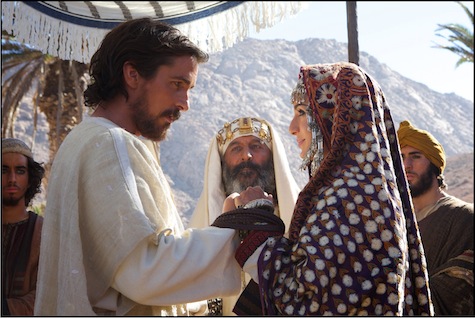

When Dreamworks made Prince of Egypt in 1998, they worked to keep the story as Biblically accurate as they could, while also deepening the relationship between Rameses and Moses for added emotional resonance, and giving Miriam and Moses’ wife, Zipporah, larger roles. Exodus does this, a little bit, but in ways that don’t completely work. When the film opens, it seems like Rameses and Moses have been raised together as brothers, with Seti giving them each a sword engraved with the other’s name to remind them of their bond. Only Rameses can inherit the throne, and Moses doesn’t want it, but there is still constant tension between them. Unfortunately, the film doesn’t really establish that they see each other as brothers as much as it shows you that they don’t trust each other, and Rameses does in fact kick Moses to the curb at the first possible opportunity. Miriam’s role is tiny (she does come across as much more tough-minded than her brother) and then she disappears from the rest of the film. The marriage ceremony between Moses and Zipporah (the film has changed her name to Sephora, but screw that, I like Zs) is actually kind of sweet. They add some interesting… personal… vows, which caused some laughter during my screening. María Valverde plays well as fiery wife-of-Moses, and their relationship is a good equal partnership, until God messes it up.

The depiction of the Ten Plagues is unequivocally great. Each new horror is worse than the last, and unlike any other depiction of this story (even the awesome Prince of Egypt) you really get a sense of the reality of the plagues. When the fish die, we see the flies and maggots billowing all over the land. The flies themselves are everywhere, and we see a man screaming as they swarm over his eyes, nose and mouth. When an ox dies suddenly, we see the owner, who was moments before yelling at the animal to behave, weeping and holding its head. We see herders on their knees surrounded by their fallen flocks, and we see people starving as their crops fail. It drives home the fact that these people are absolutely dependent on their livestock and the land that sustains them. The film also does a great job moving between the classes, showing us the plagues from the perspectives of farmers, doctors, poor mothers, wealthier mothers, basically everyone they can fit in, before checking in with Rameses and Nefertari in the palace. And the death of the firstborn children is as chilling as it should be.

The other throughline seems to be a half-hearted exploration of Moses’ skepticism. And this is where the film really fails. There’s no other way to put this. If I was God, I would sue for defamation over this movie.

Allow me to elaborate.

You know how in Erik the Viking the Vikings finally get to Valhalla and they’re all excited (except the Christian missionary, who can’t see anything because he doesn’t believe in the Norse gods) to finally meet their deities, and then they discover that the Norse pantheon is a bunch of petulant children, murdering and maiming out of sheer childish boredom? That’s the tack this movie takes. Which, in Erik the Viking, worked great! Just like the creepy child/angel who turns out to be an emissary of Satan was perfect for The Last Temptation of Christ. But for this story? You need a God who is both utterly terrifying, and also awe-inspiring. You need the deity who is capable of murdering thousands of children, and the one who personally leads the Hebrews through the desert. You need that Pillar of Fire action.

So let’s begin with the fact that God is portrayed as a bratty British child. Rather than a disembodied voice issuing forth from the burning bush, this child stands near the bush and whines at Moses about forsaking his people and orders him to go back to Memphis. You don’t get a sense that this is a divine mystery occurring, just that Moses is truly, desperately afraid of this kid. The child turns up in a few following scenes that are more reminiscent of a horror movie than anything else, which could work—getting a direct command from the Almighty would be about the most terrifying thing that could happen to a person—but since the child comes off as petulant rather than awe-inspiring, none of Moses’ decisions make any emotional sense. This man, who has been a vocal skeptic about both the Egyptian religion and that of the Hebrews, has to make us believe in a conversion experience profound enough that he throws his entire life away and leaves his family for a doomed religious quest, but it never comes through. (And let me make it clear that I don’t think this is the child actor’s fault: Isaac Andrews does a perfectly good job with what he’s given.)

After Moses returns to Memphis and reunites with the Hebrews, he teaches them terrorist tactics to coerce the Egyptians into freeing them. (Again, this isn’t in the book.) These don’t work, and result in more public executions. After seemingly weeks of this, Moses finds God outside of a cave, and the following exchange happens:

Moses: Where have you been?

God: Watching you fail

Geez, try to be a little more supportive, God. Then God begins ranting at Moses about how horrible the Egyptians are, and how the Hebrews have suffered under 400 years of slavery and subjugation, which sort of just inspires a modern audience member to ask, “So why didn’t you intervene before, if this made you so angry?” but Moses turns it back on himself, asking what he can do. At which point God literally says, “For now? You can watch,” and then starts massacring Egyptians. Moses then, literally, watches from the rushes as the Nile turns to blood and various insects and frogs begin raining down, rather than having agency as he does in the Bible.

You need the sense of constant conversation between Moses and God, the push and pull between them that shapes the entire relationship between God and his Chosen People. And for that you need a sense of Moses choosing back. In the Book of Exodus, Moses’ arc is clear: he resists God’s demands of him, argues with Him, tells him he doesn’t want to be a spokesperson, cites speech impediment, pretty much whatever he can come up with. In response, God makes his brother, Aaron, the literal spokesperson for the Hebrews, but he doesn’t let Moses off the hook: he becomes the general, the leader, the muscle, essentially—but he’s also not a blind follower. He argues for the People of Israel when God rethinks their relationship, and he wins. He is the only human God deals with, and after Moses’s death it is explicitly stated that “there arose not a prophet since in Israel like unto Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face.”

In Ridley Scott’s Exodus, Moses fears God immediately, but he comes around to a genuine sense of trust only after they’re at the shores of the Red Sea. Knowing that the Egyptians are bearing down on them, the Hebrews ask Moses if they have been freed only to die in the wilderness, and at that moment, as an audience member, I really didn’t know. I had zero sense that God cared about them as a people rather than as a convenient platform for inexplicable revenge against the Egyptians. Moses, realizing that they’re doomed, sits down at the sea’s edge and apologizes, saying that he knows he’s failed God, and only after this does the sea part. This seems to be more because of currents shifting than an act of divine intervention… because, remember the other thing everyone expects from an Exodus movie? The Parting of the Red Sea, perhaps? This movie doesn’t completely do this: the parting happens, technically, but it’s totally out of Moses’ control, and could just be a natural phenomenon.

The film skips ahead to The Ten Commandments, where we find out that God is asking Moses to carve them out in reaction to Infamous Calf-Worshipping Incident, rather than before it. This retcons the Ten Commandments, tying them to a specific incident punishment rather than guidelines that exist outside of time. And God’s reaction to that infamous Calf? A disgusted shake of his head. Like what a pre-pubescent kid brother would do listening to his big sister gush about a boy she really liked. And all of this could have been awesome, actually, if the film had a thought in its head about an evolving God, a God that lashed out at some types of oppression but not others, a God that changed His mind as time passed. You know, like the one in the Hebrew Bible.

What does it mean to be God’s chosen? This question has been explored in literature from The Book of Job to Maria Doria Russell’s The Sparrow. Buried within the books of Exodus, Deuteronomy, and Leviticus is the story of Moses’ relationship with God. Most of the books of the Hebrew Bible don’t have the sort of emotional nuance and psychological development that a modern reader expects, simply because these are cultural histories, telling huge stories, giving laws, and setting dietary restrictions that span centuries. They can’t really take the time to give everybody a stirring monologue. Despite that, the story of God and Moses does come through in the Book of Exodus, and this is where the film could fill in Moses’ inner life. Christian Bale, who can be a magnificent actor, only really lights up when he’s playing against María Valverde as Moses’ wife. The moments when he has to deal with God, he’s so hesitant and angry that you never get the sense that there’s any trust or awe in the relationship, only fear. In an early scene, Moses defines the word Israel for the Viceroy, saying that it means “He who wrestles with God” but there’s no payoff for that moment. Moses goes from being terrified to being at peace with his Lord, seemingly only because his Lord lets him live through the Red Sea crossing.

Now, if we can wrap our heads around a single person being God’s Chosen, then what about an entire people? While Exodus can be read as the story of the relationship between Moses and God, The Hebrew Bible as a whole is the story of God’s relationship with the Hebrews as a people. From God’s promise not to kill everyone (again) after the Flood, to his selection of Abraham and Sarah as the forefathers of a nation, to his interventions in the lives of Joshua, David, and Daniel, this is a book about the tumultuous push and pull between fallible humans and their often irascible Creator. However, as Judaism—and later Christianity and Islam—spread, these stories were brought to new people who interpreted them in new ways. Who has ownership? What are the responsibilities of a (small-c) creator who chooses to adapt a story about Hebraic heroes that has meant so much to people from all different backgrounds and walks of life? To put a finer point on this, and returning to my thoughts at the opening of this review: is Exodus racist?

To start, the statuary that worried me so much in the previews is clearly just based on Joel Edgerton’s Ramses, and they left the actual Sphinx alone. That said, all the upper-class Egyptian main characters are played by white actors. All of ‘em. Most of the slaves are played by darker-skinned actors. The first ten minutes of the film cover a battle with the Hittites, who are clearly supposed to look “African,” and are no match for the superior Egyptian army.

Once we meet the Hebrews we see that they’re played by a mix of people, including Ben Kingsley as Nun (the leader of the enslaved Hebrews and father of Joshua) and Aaron Paul and Andrew Tarbet as Joshua and Aaron respectively. Moses is played by Christian Bale, a Welsh dude, mostly in Pensive Bruce Wayne mode. His sister, Miriam, is played by an Irish woman (Tara Fitzgerald). Now, I am not a person who thinks we need to go through some sort of diversity checklist, and all of these actors do perfectly well in their roles, but when you’re making a movie set in Africa, about a bunch of famous Hebrews, and your call is to cast a Welsh dude, an Irish woman, and a bunch of white Americans? When almost all of the servants are black, but none of the upper-class Egyptians are? When John Turturro is playing an Egyptian Pharaoh? Maybe you want to rethink things just a little.

(Although, having said that, John Turturro’s Seti is the most sympathetic character in the movie. But having said that, he dies like ten minutes in, and you spend the rest of the film missing him.)

The other pesky racially-tinted aspect of the film is that the poor Egyptians are suffering about as much as the Hebrew slaves, and it’s extremely difficult to listen to God rail against slavery and subjugation while He’s pointedly only freeing one group from it. All the black servants will still be cleaning up after their masters the day after Passover. The Exodus story became extremely resonant to the enslaved community in America, and was later used by abolitionists to create a religious language for their movement. Harriet Tubman was called Moses for a reason. So to see a black character waiting on Moses, and knowing that he’s only there to free some of the slaves, becomes more and more upsetting. This feeling peaked, for me, when the 10th plague hits, and you watch an African family mourning their dead child. Given that the only obviously dark-skinned Africans we’ve seen so far are slaves, can we assume that this a family of slaves? Was the little boy who died destined, like the Hebrew children, for a life of subjugation? Why wasn’t he deemed worthy of freedom by the version of God this film gives us?

This just brings up the larger problem with adapting stories from the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, though. These stories adapt and evolve with us. When Exodus was first written down, it was a story for the Hebrew people to celebrate their cultural and religious heritage—essentially the origin story of an entire nation. It was a story of their people, and explained them to themselves. It reaffirmed their particular relationship with God. As time passed, and Christianity ascended, the story of Passover particularly was used to bring comfort to a people who were now being subjugated, not by foreigners or infidels, but by people who claimed to worship the same God they did. The story then transmuted again as enslaved Africans, indoctrinated into Christianity, applied its teachings to their own situations, and drew hope from the idea that this God would be more just than its followers, and eventually lead them out of their own captivity. In light of this history, how can we go back to the old way of telling it? How can we tell a tale of a particular people, when the tellers themselves seem more invested in making the plagues scary and throwing 3D crocodiles at us? How can this be a story of freedom when so few of the slaves are freed?

If we’re going to keep going back to Biblical stories for our art, we need to find new ways to tell them, and dig in to look for new insights. Darren Aronofsky’s Noah also strayed pretty far from its source material, but in ways that added to the overall story. It makes sense that Noah is driven mad by the demands of the Creator. He also dug into the story to talk about ecology, our current environmental crisis, and the very concept of stewardship in a way that was both visually striking, and often emotionally powerful. It didn’t always work, but when it did, he made a movie that was relevant to humans right now, not just a piece of history or mythology. If you’re going to make a new version of a story of freedom, you have to take into account what this story has meant to thousands of people, and what it could mean to us now rather than turning it into a cookie cutter blockbuster with no moral stakes or purpose.

Perhaps Leah Schnelbach is naive, but surely there are one or two capable actors in Egypt? You can choose to follow her on Twitter!